How to: Cycle around the world

Want to quit your job and go travelling but too skint or scared to take the leap? Take inspiration from Annie Londonderry, the first woman to cycle around the world. Coralie Modschiedler recounts her stirring tale.

On the morning of 13 January 1895, an enthusiastic crowd, giddy with anticipation, lined the streets of Marseille to see the arrival of a brave, young American woman in her early twenties.

Dressed in a man’s riding suit and astride a man’s bicycle, she had braved bitter cold and snow to reach the south of France from Paris. But despite the hardship, there she was, in the flesh: the famous, audacious Annie Londonderry – the first woman to attempt to cycle around the world.

A loud cheer went up and people waved and shouted as the petite, dark-haired cyclist wheeled by with one foot – her other foot, wrapped in bandages, was propped on the handlebars. Marseille was the last leg of her French sojourn and had been the most perilous so far.

“One night I had an encounter with highwaymen near Lacone [about 50km north of Marseille],” Annie later wrote in the New York World.

“There were three men in the party, and all wore masks. They sprang at me from behind a clump of trees, and one of them grabbed my bicycle wheel, throwing me heavily.

“I carried a revolver in my pocket within easy reach, and when I stood up I had that revolver against the head of the man nearest me. He backed off but another seized me from behind and disarmed me. They rifled my pockets and found just three francs.

“My shoulder had been badly wrenched by my fall, and my ankle was sprained, but I was able to continue my journey.”

Annie was a bold spirit who reinvented herself against all odds

Annie was a bold spirit who reinvented herself against all oddsPeter Zheutlin

While the dramatic encounter with highwaymen quickly became a staple among Annie’s many stories, it was never mentioned in the local press.

There was of course another explanation for why Annie pedalled into town with one foot wrapped in bandages – the inflammation of her Achilles tendon a few days earlier – but surviving a dramatic robbery made a much better story.

Annie never let the facts get in the way of a good tale. By then, she was reportedly halfway through a 15-month bike ride, a challenge she was undertaking to settle an extraordinary, high-stakes wager between two wealthy Boston businessmen.

If she could cycle around the world in that time and manage to earn $5,000 during her travels, she would earn an additional $10,000 on her return.

Her celebrity status was on the rise and the French press had been writing about her prolifically since her arrival at the northern port of Le Havre in December. She was a legend in the making.

Unbeknownst to the crowd of admirers who had gathered to see her in Marseille, the young cyclist from Boston was in fact Annie Cohen Kopchovsky, a married Jewish working mother of three.

What’s more, Annie was not just a cyclist on a round-the-world tour, but a consummate self-promoter and inveterate storyteller who was about to turn her journey into one of the most outrageous chapters in cycling history and herself into one of the most colourful characters of the 1890s.

“I didn’t want to spend my life at home with a baby under my apron every year,” she would often say.

With the cycling craze and women’s movement for social equality in full swing in the mid-1890s, the bicycle represented to Annie a literal vehicle to the fame, freedom and material wealth she craved.

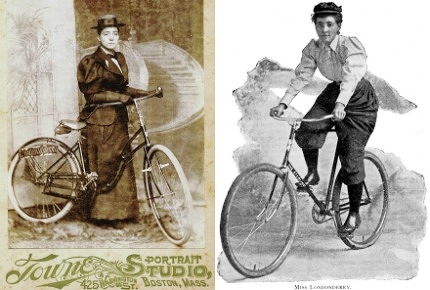

Annie staged this photograph to illustrate her lectures

Annie staged this photograph to illustrate her lecturesPeter Zheutlin

The rest of her journey, which would take her all over Asia and back to the US via the harsh Southern California desert, would be filled with harrowing adventure, frequent danger and endless drama.

Her increasingly outlandish tales – from witnessing the First Sino-Japanese War, to encountering one of the most infamous outlaws of the Old West, John Wesley Hardin, to being run over and almost killed in California – would soon attract increasing doubt over her alleged exploits.

“I shall never forget the horrible scenes I witnessed at Port Arthur. We arrived there after the butchery, but the dead remained unburied. I saw the bodies of women nailed to the houses, the bodies of little children torn limb from limb,” Annie told the New York World.

“[W]e were captured by the Japanese and were thrown into a cell, and left without food for three days.

“While thus imprisoned a Japanese soldier dragged a Chinese prisoner up to my cell and killed him before my eyes, drinking his blood while the muscles were yet quivering.”

Was any of it true? Almost certainly not. Annie knew how to spin a yarn.

It sure was a very lucrative business – her popular history lectures, signed photographs and advertising space on her bike generated more income than she had ever earned as a journalist back in Boston.

Whether she was viewed as a hustler making a buck, as in Singapore, or as a free-thinking young woman making a statement, as in Saigon, it’s clear that Annie made an impact wherever she travelled.

Annie cared little about the negative press. From her point of view, the more ink she got, the better.

For the thousands of people she met along the way, and countless others who read about her, Annie’s journey created memories of a smart, vivacious, charismatic and fiercely independent woman, memories that no doubt lasted a lifetime as they did for Annie – who of course completed the journey 15 months to the day she set off in Boston.

Annie Londonderry’s incredible journey is told in Peter Zheutlin’s thoroughly researched Around the World on Two Wheels (2007), which is published by Kensington Publishing Corp and available to purchase online.

Enjoyed this article? Then you might also like:

How to: Survive on a desert island

How to: Hike solo across Africa

Do you have any Feedback about this page?

© 2026 Columbus Travel Media Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this site may be reproduced without our written permission, click here for information on Columbus Content Solutions.

You know where

You know where